'Take Me Out' review — uneven play falls short of a home run

Richard Greenberg's Tony-winning play Take Me Out returns to Broadway, urging the audience this time to be fully present. From the moment one walks into the Hayes Theatre, ushers command patrons to turn off cellphones and lock them away in a Yondr pouch — a secure device that remains sealed until everyone leaves the theatre. This precaution occurs for many reasons, but the most important is to protect the actors who occasionally appear fully nude. Unfortunately for this disjointed slow burn, the play's X-rated factor becomes the audience's talk point, a major distraction that causes some to miss the message or overlook it entirely.

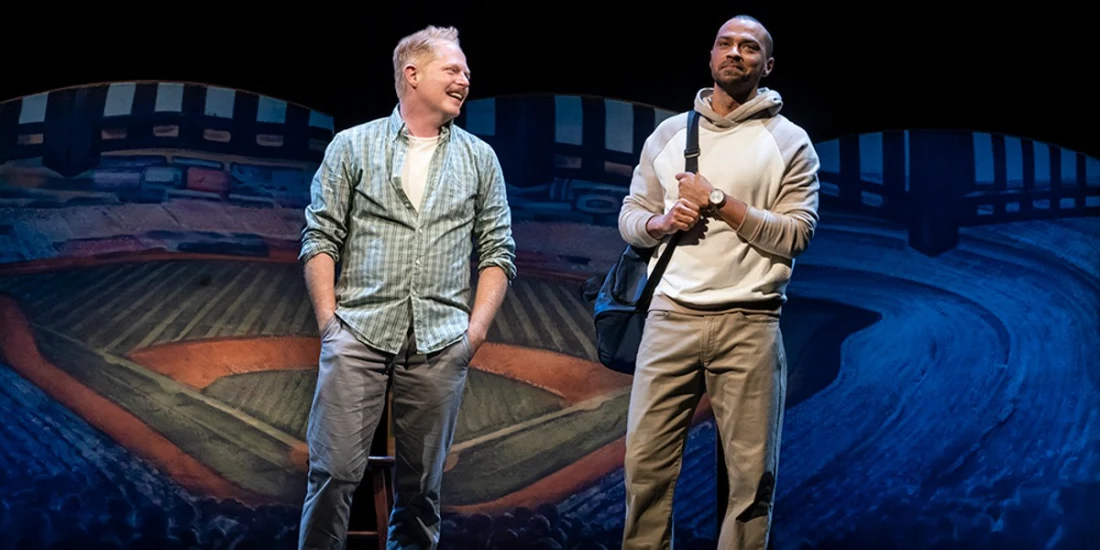

It's the 2002 baseball season and inside the Empires' locker room is a coming-out story. Star player Darren Lemming (a one-dimensional but overconfident Jesse Williams) is idolized as one who had the best of everything — "a Black man who never suffered." That is, until the day he comes out as gay. The guy who once served as his team's champion and beacon of all things "macho American sports" becomes dimmed down to a dude searching for identity, and he himself is buried in a story with its own identity crisis.

Under the uneven direction of Scott Ellis, Take Me Out becomes a cluster of both remarkable and insignificant performances pieced together inside a scattered plot. The story's dramatic turns quickly evolve into humor and fluff. Though Jesse Tyler Ferguson gives one of his best performances to date as Mason Marzac, the audience is never allowed time to sit with the dramatic moments his character's comedic presence often follows.

What Take Me Out does right is highlight how sportsmen, entrenched in a business that boasts the traditional expectations of masculinity, respond to a team member's homosexuality. The reactions move from open support to microaggressions to downright hostility. Oddly enough, the story that Greenberg wants us to pay attention to takes a back seat to the man who verbally causes Lemming the most harm. Michael Oberholtzer as Shane Mungitt, the team's new pitcher and unapologetic bigot, is the character that serves the audience uncomfortability and sympathy. I found myself questioning how this character became this way instead of focusing on the harm he causes Lemming and the rest of his team.

Slow to bat, this play's second act serves as its home run. Inside the team showers, beautifully crafted by David Rockwell, a place of vulnerability (and nudity) marks the show's most memorable turning point. A private moment between Lemming, who until this moment was proud and confident, confronts Mungitt, exposing both characters' demons. What comes after is both tragic and enlightening.

However, Take Me Out is not as relevant today as it was 20 years ago. In the history of Major League Baseball, only two players have come out as gay: Glenn Burke and Billy Bean. Today, each of America's big five sports categories currently has an openly gay man in the pros (though baseball's is in the minor leagues, not the MLB). We still have a long way to go in terms of our perception of masculinity — or what it even means to be male — and Take Me Out makes us aware of this, but uses a curve ball to do so.

Photo credit: Jesse Tyler Ferguson and Jesse Williams in Take Me Out. (Photo by Joan Marcus)

Originally published on